This is the video and transcript of a talk I gave recently, about the need to develop a more granular approach to describing the arts. I was asked to speak at the second Tramway World Cafe, produced by PAL Labs in association with MMM and Tramway, responding to this question: What can we do to support artists to maintain their practice, integrity and enquiry while making that wider contribution to our meaning, values and process at this critical time in our personal, professional, national and global lives?

…

Suzy Glass from Mission Models Money on Vimeo.

I’m going to spend my time up here talking about how we might find better ways of talking about what we do, focussing on how we persuade society at large that these ways of working are of value.

This is still early-stage thinking, brought into hazy relief about a month ago when Roanne asked me to do this. While much of it’s been drifting around jelly-like in my head for a number of years, this is the first time I’ve attempted to reign it in and give it a cohesive shape.

Bits of it don’t feel quite right yet. But hopefully enough of it will resonate, providing a point from which to refine further, letting us develop a clearer narrative to help carve out properly resourced spaces in which artists, designers, makers are able to apply themselves in order to influence, reflect and manifest the values of the world at large.

Last week I spent 5 days in Dungeness. I was staying in this very beautiful building.

It’s called the Shingle House and it was designed by Glasgow-based architects Nord as part of Alain de Botton’s Living Architecture initiative.

I was there with six other women, all of them wonderful, committed, inspiring people. Between us we work variously and fluidly across two or more of the arts, social innovation, government, the creative industries and the screen industries, both as practitioners – doers – and also as designers of policy and strategy – thinkers. We had come together to attempt to spend some time reflecting on what we do, how we work, and why.

All seven of us were in agreement that society needs high-level creativity in order to function effectively. Given this, I found myself surprised by our inability as a group to talk cogently with one another about the role the arts play and can play in this world we live in.

Interestingly, we had fewer problems talking about design: we were all able to understand how design and design thinking have systemically and structurally impacted on and in some cases influenced change in society. Possibly this is because design operates much more cleanly as a sector that deals with problem-solution scenarios?

Anyway, when it came to the arts, to artists and their role, conversation tended to falter and occasionally break down. I found myself attempting to hold things together by citing examples of instances when specific artists have directly or indirectly done something vital. So I talked for example about Ellie Harrison, who for those of you who don’t know is a visual artist based here in Glasgow. She uses her artistic practice as a campaigning tool, dealing with issues including environmental sustainability, austerity, the gradual erosion of our public services.

This is Early Warning Signs, a piece by Ellie that’s currently touring the UK, promoting their cause by sitting outside host venues, including GOMA throughout 2014.

While such examples are always interesting – that goes without saying – they hardly form a rigorous argument for the fundamental necessity and importance of an arts sector. It’s too piecemeal an approach.

I also threw lofty and unsubstantiated claims into the mix. I heard myself say at one point “well artists can think differently, can’t they?” Which is something I do believe. But I’m not wholly sure what I mean. And as a statement it’s hardly going to wash with a sceptic is it?

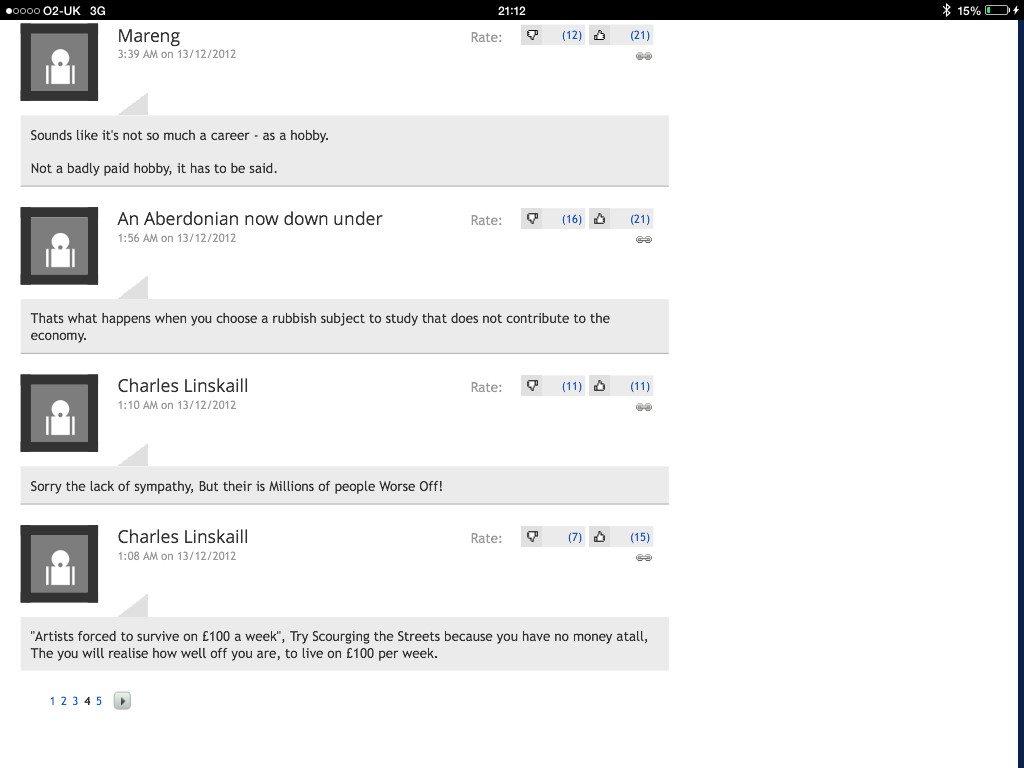

Crucially, what both of my chosen approaches failed entirely to deal with was a core confusion within the group about the scope, stretch and diversity of artistic practice. Again, bear in mind that I was in conversation with broadly sympathetic people. Not your average Daily Mail reader…or in fact Guardian or Scotsman reader given some of the vitriolic comments I’ve stumbled across recently.

These comments are responding to a piece published in the Scotsman last year about a Scottish Artists Union survey of the income of visual artists. The survey found that 75% of its members earn less than £5000 per year. Which – according to a large number of the 66 people who chose to comment – is just about right because all artists are insular hobbyists who contribute very little to society.

This is the reality: people find it very easy to interpret ‘The Arts’ as this monolithic thing, sitting outwith the real world, practiced by a few lucky people who have somehow managed to persuade the world that they deserve to noodle about with their guitars or paintbrushes all day. The general public still perceive ‘The Arts’ to be exclusively populated by individuals who are removed from society making objects or events that aren’t for, of, with, about or relevant to them.

If we continue to perpetuate this singular narrative, if we carry on talking in grand, generic terms about ‘The Arts’, then we’re bound to keep struggling to communicate our worth as a sector.

So I’ve started thinking about a more granular approach to describing the various things we all do. Of course, we already use discipline descriptors to create sub-divisions: dance, visual art, product design, documentary etc. I think we need more than this though. I’m interested in developing a set of signifiers to sit alongside discipline descriptors that refer to the range of intention and / or ways-of-working that exist within creative practice. I want to find a way of reflecting the fact that we’re not all setting out to do and achieve the same thing.

For instance – and these terms are by no means the right one, but it’s a start – the primary motivation behind artwork A might be to entertain, while artwork B is motivated by a desire to educate. Artwork X was created primarily to affect social change, Artwork Y meanwhile was motivated by the need to document a moment in time.

These are all equally valid, useful and important motivating factors. But while entertaining and documenting might make it into person-on-the street’s definition of ‘The Arts’, the others probably wouldn’t. Which, to return to one of the questions underpinning today’s symposium, makes it incredibly difficult for artists to lead cultural change and influence values. If we continue to fail to communicate to people the diversity of intent underpinning arts practice, we will continue to struggle to create opportunities to work meaningfully and equally with our peers working in other sectors.

We do of course have some terms we’re already using, with some degree of success. Participatory practice for instance. But they’re terms that stand by themselves, they’re not embedded within a rigorous framework. This means they’re perceived and often judged to be other, different, not the actual thing itself.

It’s only once we develop and take ownership of a full spectrum of terms that we’ll create a structural understanding of the complexity of arts practice. We’ll begin to present ourselves as a sophisticated sector that’s balanced, complete and manifestly diverse in terms of intent, practice and ultimately impact. It’s not an easy ask: it’s going to take effort and undoubtedly a long time to develop a set of terms that we can all, in the main, feel comfortable signing up to and using.

But if we manage to develop and communicate this nuanced, sophisticated framework, using language that feels appropriate and expressive, the rewards will be manifold. We’ll be able to apply our practice on our own terms, avoiding instrumentalisation by other sectors and instead collecting around the table as peers. This is important: having your work and practice instrumentalised is very different from applying your work and practice. If we manage to talk about our sector in more granular terms, we’ll develop new working relationships and environments by virtue of the fact that people will be able to understand more clearly how artistic practice might be relevant and useful to them.